|

The Zero Anthropology Project

Webfolio for Maximilian C. Forte

HOME |

SITE MAP |

ABOUT

| RESEARCH |

MEDIA |

ARTICLES |

REVIEWS |

COURSES |

ZAP SITES |

CONTACT

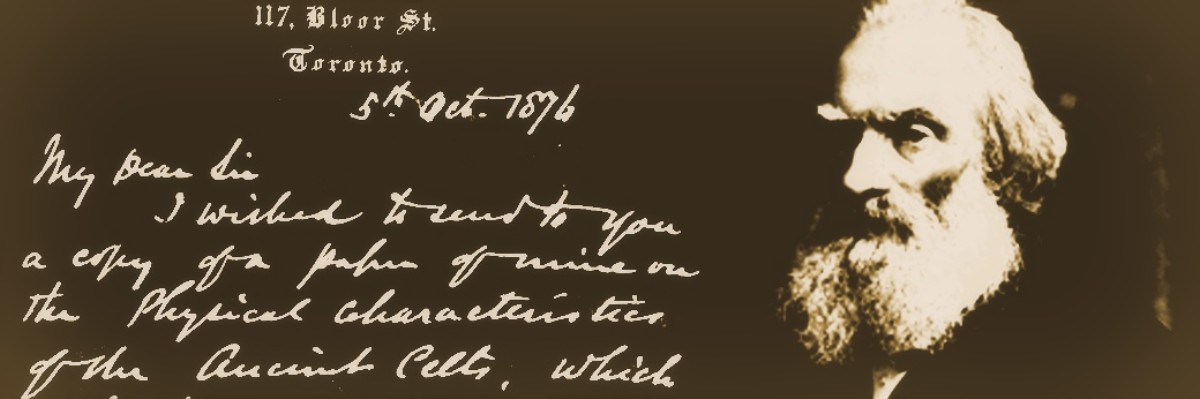

This is an edited and abridged version of an an

article that

appeared on

Zero Anthropology.

When

it comes to anthropology, Canada is the home of

a number of “firsts”. The first courses

in anthropology offered in any university in the

world, were offered in Canada: they were taught

by

Sir Daniel Wilson at the

University of Toronto (Van Esterik, 2006, p.

261)—in the photo at right. Daniel Wilson was

also the world’s first professional,

university-based anthropologist (Hancock, 2006,

p. 36). The first PhD in Anthropology in all of

North America was earned by A.F. Chamberlain, a

Canadian (Cole, 1973, p. 40). When

it comes to anthropology, Canada is the home of

a number of “firsts”. The first courses

in anthropology offered in any university in the

world, were offered in Canada: they were taught

by

Sir Daniel Wilson at the

University of Toronto (Van Esterik, 2006, p.

261)—in the photo at right. Daniel Wilson was

also the world’s first professional,

university-based anthropologist (Hancock, 2006,

p. 36). The first PhD in Anthropology in all of

North America was earned by A.F. Chamberlain, a

Canadian (Cole, 1973, p. 40).

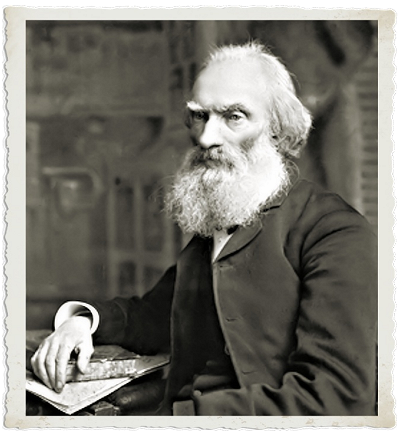

Sir

Daniel Wilson—as Canada’s and the world’s first

university-based professional whose teaching,

research, and writing focused on explicitly

anthropological topics—was responsible for first

developing the very topics of Canadian

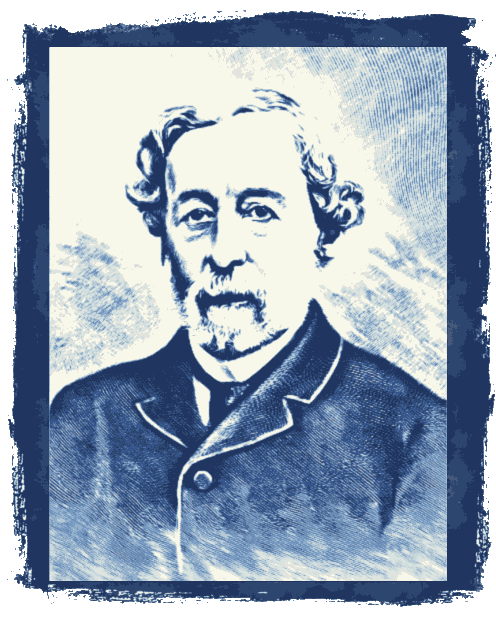

anthropological study. Both Wilson, and then

Horatio Hale (portrait, left)

soon after, pioneered an intellectual tradition

that was in some ways a precursor to what

developed later in the US (thanks to Franz Boas

who worked under Hale in Canada), but also

remained relatively unique. Sir

Daniel Wilson—as Canada’s and the world’s first

university-based professional whose teaching,

research, and writing focused on explicitly

anthropological topics—was responsible for first

developing the very topics of Canadian

anthropological study. Both Wilson, and then

Horatio Hale (portrait, left)

soon after, pioneered an intellectual tradition

that was in some ways a precursor to what

developed later in the US (thanks to Franz Boas

who worked under Hale in Canada), but also

remained relatively unique.

One can only guess what Canadian anthropology

would have been, had there been continuity in

development building on the foundations laid by

Wilson and Hale. We might be exactly where we

are today, where anthropology in Canada is

largely an import shaped by professionals who

were either trained in the US or the UK, and

where many of the teaching materials are

similarly imported. Another possibility is that

Canadian anthropology would have been present in

universities, but not as a distinct discipline

that occupied space in the form of departments.

This essay builds on the second vein.

Theoretical Foundations of a Canadian

Anthropology

Some of the key theoretical developments common

to Wilson and Hale include: a non-racist

and a non-linear theory of cultural

change; cultural relativism; and, a multi-field

approach (that included linguistics and

archaeology). In addition, the Canadians were

deeply embedded in public communications, would

frequently address public audiences at schools,

libraries, museums, or in the press, and in this

sense they innovated a form of “public

anthropology” before the phrase even existed.

Neither of them practiced anthropology as a

“discipline”: at the University of Toronto,

courses in ethnology were offered in a variety

of programs, while Hale did not work in a

university setting.

If we were to summarize their innovations, we

would have the following as a rough list:

-

The term “prehistory” was first coined by

Daniel Wilson (Cole, 1973, pp. 33, 35).

-

Daniel Wilson did not accept the idea of

either unilineal or unidirectional evolution

(Trigger, 1966, p. 13); Hale; rejected

evolutionary stage theory (Cole, 1973, p.

39).

-

Daniel Wilson argued that it was possible

for a society to pass from a more advanced

to a more primitive state, thus breaking

with the teleology of cultural evolutionism

(Trigger, 1966, p. 13). Things could indeed

fall apart.

-

Daniel Wilson rejected the theory that one

could explain cultural and even linguistic

differences in terms of racial variation

(Trigger, 1966, p. 21).

-

Daniel Wilson demonstrated that cranial

capacity did not provide a gauge of

intellectual capacity, countering the

assumptions of early physical anthropology

(Cole, 1973, p. 35).

-

Daniel Wilson argued that “primitive

peoples” have the same intellectual

capacities as “civilized” peoples, “and he

refused to consider the state of a culture’s

development to be an indication of the

intellectual ability of its members”

(Trigger, 1966, p. 12).

-

What came to be known elsewhere as “cultural

relativism” was developed first in Canada,

in the works of both Wilson and Hale

(Trigger, 1966, p. 14; Cole, 1973, p. 39).

-

There was a strong critique of racism as

found in the American School of Ethnology,

by Daniel Wilson (Trigger, 1966, p. 15);

Horatio Hale likewise criticized

ethnocentric prejudice, at a time when such

prejudice was a foundation of British and US

ethnology (Cole, 1973, p. 39).

One

might speculatively extrapolate from these

foundations. To begin, their rejection of

the kind of progressivist, liberal, “cultural

evolutionism” that has dominated mainstream

political and economic thought in North America,

would have directed Canadian anthropology to

reject modernization theory and neoliberalism.

Canadian anthropology would have had nothing to

do with “development studies”. Canadian

anthropology would have been equally inclined to

reject “peace-building,” the “responsibility to

protect,” “humanitarian intervention,” and

“democracy promotion”—key ideological supports

for imperialist policies of regime change and

de facto recolonization. One

might speculatively extrapolate from these

foundations. To begin, their rejection of

the kind of progressivist, liberal, “cultural

evolutionism” that has dominated mainstream

political and economic thought in North America,

would have directed Canadian anthropology to

reject modernization theory and neoliberalism.

Canadian anthropology would have had nothing to

do with “development studies”. Canadian

anthropology would have been equally inclined to

reject “peace-building,” the “responsibility to

protect,” “humanitarian intervention,” and

“democracy promotion”—key ideological supports

for imperialist policies of regime change and

de facto recolonization.

Paternalistic and ethnocentric approaches to

international affairs, which involve the “most

developed” extending a “helping hand” to speed

up the “least developed” in “bridging” the “gap”

in consumption, governance, and so on—would have

been tossed out by Canadian anthropology, at the

very least for being unscientific. Likewise, the

notion of “American exceptionalism” would have

been torn asunder by Canadian anthropology. It

is fundamentally an expression of progressivist,

ethnocentric prejudice.

Second, Canadian anthropology would not

have allowed for the race-fixation that has

become dominant in the US. The incessant

racialization of analysis of social relations

would thus have found no fertile ground for

development in Canadian anthropology, nor the

competitive identity politics that play a

central role in neocolonial/neoliberal

divide-and-rule strategies.

Third, Canadian anthropology would not

have developed separate from other

disciplines—since it would not have been a

discipline itself. It would have instead become

a fertile field for combining the methods and

insights of a wide range of intellectual

endeavours, all driven by a basic aim of

explaining how human societies come together in

given places and times, how they cohere and fall

apart, and how members of many different

national societies interact in creating new

societies. Hale, and Wilson especially, were

interested in issues of cultural

transplantation, hybridization, and demographic

migration—the kinds of large-scale processes

that have historically been brought about as a

result of the work of empire.

“what kind of anthropology is there,

that is even worth having?”

The

questions, the topics, the concerns would have

been of the “biggest” kind, particularly

following Wilson—anthropology would have leaned

more toward the nomothetic side (for

more, see

this and

the other article on the ZAP site).

Certainly the study of empire would have

been particularly welcome in a Canadian

anthropology that was interested in

understanding and explaining the forces at work

in shaping human lives, human social orders, and

human futures. Imperialism has been the

largest-scale force responsible for undoing,

repacking, and reinventing societies, how they

are governed, what they produce and why they

produce certain products, and for significantly

affecting the quality of human lives. Without

such an interest, what kind of anthropology is

there that is even worth having?

The Parameters of a Canadian Anthropology

The

shape of Canadian anthropology, on the

foundations laid by Daniel Wilson, had at least

the six following, and very notable features:

-

Multi-disciplinarity: Canadian

anthropology did not originate as an

independent discipline in universities. It

was always, from its earliest beginnings,

part of a field of inquiry conducted by

persons in multiple disciplines. Even when

institutionalized in universities, Canadian

anthropology was housed in

multi-disciplinary schools of social

science, and to this day about a third of

all anthropology programs in Canada remain

wed to sociology.

-

Public communication: Wilson, Hale,

and their contemporaries saw their teaching

mission as extending to public lectures in

schools, museums, and seminaries. They

sought out the press. This was done as if a

normal part of the routine, which upsets any

preconception of the Canadian university as

either always or only an “ivory tower”

institution. Canadian anthropology was a

public mission.

-

History—the Long-Term: Wilson’s work

shows a keen interest in grasping large

sweeps of time, in seeing cycles where

others saw unidirectional progress. This

interest in rise and fall is also

well suited to the study of empires.

-

Large spaces, large movements—the

Large-Scale: Wilson’s focus on the

encounters of large masses of different

peoples, brought from different continents,

complimented his interest in long time

frames.

-

No kinship: Kinship was not a subject

of concern to Wilson. Instead, as was

convincingly explained by

Adam Kuper, the

lead historian of British anthropology,

kinship took shape as a subject of concern

to a particular, Victorian English social

class. There is nothing “universal” about

the origins or applicability of this

interest.

-

Independent of the US: Wilson asked

his own questions, and developed his own

ways for answering them. This was done by

remaining largely out of communication with

US and European anthropology.

From the above, we can distil a number of key

lessons for the development of an intellectually

independent, non- or anti-imperial Canadian

anthropology.

Practical Foundations for the (Re)Development of

a Canadian Anthropology

We

know a number of things about the working lives

of Daniel Wilson and Horatio Hale, that would

seem to furnish clues about their intellectual

development. For example:

-

Wilson particularly, and to some extent

Hale, either had strained or distant

relationships with their US counterparts

(Trigger, 1966, pp. 23, 26).

-

There was, at best, a remote connection to

European intellectual currents of the time

(Trigger 1966, p. 23).

We

are essentially dealing with two issues:

localization and innovation,

occurring together. How can this be achieved?

From the examples of Wilson and Hale, the

following interpretations might provide some

guidance:

(A) Distance from origins: though both

Wilson and Hale were schooled in Europe and the

US respectively, they also grew apart from those

original experiences, with both time and

distance, until they were no longer in the

mainstream of circulating currents in those

places.

(B) Filtered memories: with time, what

was once very influential in one’s intellectual

formation, can become rarely revisited sediment,

or it can even be lost.

(C) Aberrant mutations: mutations perform

a vital role in any evolutionary process. There

can be epistemic mutations as well, that thrive

in isolation, especially given free space in

which to grow. Dialogue is very important, but

so is a period of silence. Silence can perform a

role similar to radioactivity, in transforming

ideas that were barely held consciously and

which suddenly come to the fore in a new shape.

(D) Relative isolation: neither Wilson

nor Hale were formed in isolation from the

centres of learning. However, they both matured

in later years apart from such centres. This may

not have caused them to think

independently, but it was certainly present in

the process.

(E) Instability, chaos, upheaval: both

Wilson and Hale underwent some difficult

separations and transitions, finding themselves

in unfamiliar surroundings, far from home, yet

making a new home for themselves. Hale married a

Canadian, integrated into his community, and

immersed himself in local research. Wilson’s

mind shifted from Scotland to Aboriginal North

America. Their life experience would have taught

them to take little for granted and to see

stability as only momentary and fragile. Such

life experiences work against the ossification

of thought, against the comforts of hegemonic

knowledge, against disciplinary doxa.

(F) Charismatic idiosyncrasy: to fashion

a new program of teaching and research, to give

it both institutional form and make it a subject

of public fascination, requires a certain amount

of courage. Published research on Wilson and

Hale frequently alludes to their idiosyncratic

qualities, the strong nature of their individual

personas, and their tendency to launch

themselves into the public arena as educators.

“a Canadian anthropological approach

to

the study of empire and the human condition”

Hopefully, with what has been outlined above, it

might now be clearer why the “slogan” of Zero

Anthropology is, “a Canadian anthropological

approach to the study of empire and the human

condition”. Another way of seeing it is, in the

wry words of a colleague: “a tradition that

isn’t one”.

References

Cole, Douglas. (1973). “The Origins of Canadian

Anthropology, 1850-1910”. Journal of Canadian

Studies, 8, 33–45.

Forte, Maximilian C. (2017). “Canada,

First in Anthropology”. Zero

Anthropology, July 3.

————— . (2014). “Anthropology:

The Empire on which the Sun Never Sets (Part 1)”. Zero

Anthropology, May 16.

Hancock, Robert L.A. (2006). “Toward a

Historiography of Canadian Anthropology”. In

Julia Harrison & Regna Darnell, (Eds.),

Historicizing Canadian Anthropology (pp.

30–43). Vancouver: UBC Press.

Nock, David. (2006). “The Erasure of Horatio

Hale’s Contributions to Boasian Anthropology”.

In Julia Harrison & Regna Darnell, (Eds.),

Historicizing Canadian Anthropology (pp.

44–51). Vancouver: UBC Press.

Trigger, Bruce G. (1966). “Sir Daniel Wilson:

Canada’s First Anthropologist”.

Anthropologica, 8(1), 3–28.

Van Esterik, Penny. (2006). “Texts and Contexts

in Canadian Anthropology”. In Julia Harrison &

Regna Darnell, (Eds.), Historicizing Canadian

Anthropology (pp. 253–265). Vancouver: UBC

Press.

Image: Sir Daniel Wilson, and an

extract from one of his letters. Created by

Maximilian C. Forte using materials in the public

domain.

HOME |

SITE MAP |

ABOUT

| RESEARCH |

MEDIA |

ARTICLES |

REVIEWS |

COURSES |

ZAP SITES |

CONTACT

©

2011-2020, Maximilian C. Forte.

|