|

The Zero Anthropology Project

Webfolio for Maximilian C. Forte

HOME |

SITE MAP |

ABOUT

| RESEARCH |

MEDIA |

ARTICLES |

REVIEWS |

COURSES |

ZAP SITES |

CONTACT

This is an edited version of what was previously

just a collection of notes and abstracts. All of

the items referenced in the

previous version are listed in the

bibliography below.

The Structures of

Knowledge and the Future of the Social Sciences:

Where does Zero Anthropology Stand?

Writing in the Journal of World-Systems

Research in 2000, Richard E. Lee advanced

two major claims. The first was that the (re)production

of the structures of knowledge is a process that

was constituted by the modern world-system, and

that helped to constitute that same system in

return. Put in the language of the Zero

Anthropology Project, this means that

Western imperial domination generated its own

knowledge system (housed in universities), and

that such knowledge as was developed in modern

universities often tended to support, validate,

enable, or otherwise made use of imperial

domination for its own ends. Lee’s second claim

was the social sciences emerged in the 19th-century

(which is correct), as “a medium-term solution

to the tensions internal to the structures of

knowledge”. What we can say is that may be one

reason; another reason was that ruling classes

required a system for managing change—the famous

problem of order was central here. Lee

then offered two propositions: one was that “the

structures of knowledge have entered into

systemic crisis,” and the second was that, “the

uncertainty of the future opens up the character

of knowledge production and the definition and

role of the knowledge producer”. Placing this

again in the language of the Zero

Anthropology Project: Western knowledge

production in universities has entered a

prolonged period of disarray, self-doubt,

self-criticism, with struggles over the

definition of disciplines and their reason for

being, and numerous debates about their methods.

In such a period of instability and volatility,

knowledge production itself is being opened to

serious change (in both positive and troubling

directions), and the role of knowledge producers

is itself being opened to change.

As Immanuel Wallerstein long argued, “the

division of social analysis into three arenas,

three logics, three levels—the economic, the

political, and the sociocultural,” a division

which is a legacy of 19th-century

Western social science, is one of the biggest

impediments to the development of new structures

of knowledge. What was bequeathed to us from 19th-century

Western knowledge production was a division

between the humanities and their idiographic

epistemology (emphasizing the particularity of

social phenomena, the limited utility of

generalizations, and the need for empathetic

understanding), versus the natural sciences and

their nomothetic epistemology

(emphasizing the search for universal laws, for

generalizations, and for explanation). Social

science, having no epistemology that was

uniquely its own, was caught between the two—and

we see the exact same struggle occurring within

anthropology. For Wallerstein, this is a

productive tension, as discussed below. Put

simply, Wallerstein advocates for the fusion of

the two poles, rather than continuing a struggle

to no good end. Similarly, the Zero

Anthropology Project directly challenges

conventional, doctrinaire formulations of

anthropology as limited to a particular method,

focused on particular places and social units,

and limited to only certain questions. If anyone

thus asks, “but how is it anthropology?”—they

are in fact asking a good question, one that is

good for indexing the degree to which Zero

Anthropology is challenging and moving

beyond the limitations of 19th-century

knowledge structures.

“Zero Anthropology is not limited to

one method,

to studying certain places, asking only certain

questions”

Those in the world-systems camp argue for

analysis of the large-scale and the long-term—in

other words, Space and Time—as the main avenue

for transcending the arbitrary divisions of the

past. In the case of the Zero Anthropology

Project, this translates into the study of

empire in a holistic fashion, that does not

emphasize any one place of study, or any

one domain: everything, from everyday life,

entertainment, material consumption, rituals,

media, political discourse, diplomacy, the

military, and learning, are all part of the

study of imperialism as a social system, because

that is precisely how imperialism operates in

the real world.

In a separate article Lee defined the structures

of knowledge of the modern world as, “those

patterns of what can and cannot be thought that

determine what actions can and cannot be deemed

feasible in the material world”. It is these

patterns that are undergoing a transformation.

At the time he wrote, Lee (and Wallerstein)

believed that two knowledge movements—cultural

studies with roots in the humanities, and

complexity studies in the

sciences—challenged the separation of the

sciences, social sciences, and the humanities.

These two knowledge movements disrupted the

basic assumptions that allowed for these

mutually exclusive epistemologies to develop. In

yet another article, Lee was hopeful that

“direct advocacy,” and the erosion of

“professional neutrality,” would open

possibilities not just for new forms of

collaboration between agents that were

previously separated in hierarchies (such as

professors and students), but also new ways of

interpreting the world and envisioning

alternative actions. Since values and interests

have always been invested in knowledge

production, then any changes to knowledge

production are bound to become the centre of

real struggles and conflict. Authority and

legitimacy will themselves become subject to

exposure and criticism.

Indigenous

Knowledge and Decolonization: Where does Zero

Anthropology Stand?

Before proceeding, and in the interest of

absolute clarity, Zero Anthropology does

not presume to decolonize Indigenous minds,

primarily because the main thrust of Zero

Anthropology and most of its authorship, is

itself Western. For Zero Anthropology to

claim that it is in any way advancing

decolonization, would be an act of obvious

exploitation of the right to speak on others’

behalf, which is precisely one of the problems

of received/colonial anthropology. Instead, the

position of Zero Anthropology is a

sympathetic one—it is based on acknowledging

parallel transformations in the structures of

knowledge that can complement each other. Where

some emphasize decolonization and

post-colonialism, we instead emphasize

anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism.

The latter can be fully Western, without

trampling on the self-representations of others

or trying to taken them over, and is open to

uniting with others based on the objective

observation that empire is deleterious

for majorities on both sides of the imperial

divide. Imperialism does real damage to all

societies and their political and economic

systems, not to mention the distortion of their

cultures, which is the case whenever aggression

is married to exploitative accumulation. Pain

and rewards may not be distributed equally on

both sides of the imperial divide (the divide

between centre and periphery), but that does not

mean that the human damage done by empire is

ever limited to just one place or people. And

why does Zero Anthropology even care?

Because it emerged from within a public

university system, that was intended to be at

the service of the public—and that it would be a

major disservice to the public to deceive it

into believing that imperialism can produce a

good, sustainable way of life, that promotes

peace and justice.

What complicates the stance of Zero

Anthropology, as just described, is that the

author’s intellectual biography includes a

significant degree of input from Caribbean and

Latin American influences. Having lived and

studied in the Caribbean, and having been

exposed to the teachings of the New World Group,

which is an independent tradition in Caribbean

political economy, plus friendships and

collaborations with Trinidadian friends and

mentors over the years, means that there is no

clear-cut division between Zero Anthropology

as located in the imperial semi-periphery

(Canada), and its development shaped by both the

imperial periphery and the imperial centre

(given that the author was also trained in the

US). Perhaps this is why the author has

gravitated towards Atlantic Canada, which is

like a bridge between two imperial peripheries

linking Canada and the Caribbean.

So what is happening with Indigenous

Knowledge and decolonization that should

interest us? One theme is that the recovery

of Indigenous Knowledge is an act of

decolonization in rejecting Western guardianship

over all knowledge. It is an attempt to deny the

West the power to speak for the whole world. In

that spirit, Indigenous scholars are trying to

bring diverse ways of knowing to the forefront,

as valid epistemologies in their own right.

“The limits of Western knowledge are

also limits on

the authority and credibility of ‘experts’”

A

second theme in the restoration of Indigenous

Knowledge is also a means of reminding all of us

of the limits of Western knowledge, and

therefore of the limited ability and authority

of the so-called “experts”.

A third theme is one that recognizes how values

and interests have always been invested in

knowledge production as a means of acquiring or

projecting power—except that in this case

Indigenous Knowledge is about confronting the

colonizing control of states and governments.

Scholars writing on the third theme focus on

treaties as part of Indigenous Knowledge, and

emphasize the need for peaceful and just

coexistence. This third theme of the revival of

Indigenous Knowledge focuses on the production

of knowledge as a part of an anti-colonial

effort.

A fourth theme focuses on the development of

Indigenous Knowledge as a discipline, that has

its own theoretical and methodological tools.

Whether “discipline” is the right word or not in

this case is a significant issue, since the

concerns of Indigenous Knowledge span a wide

range of issues that have been historically

apportioned to different and even competing

disciplines. These issues include everything

from spiritual, emotional, and physical health,

to stewardship of the land, to autonomous

self-government. The result of such an effort

would be the creation of an internationalized

field of study known as Indigenous Studies.

* For more on Zero Anthropology and

decolonization, see the

Articles tab in the menu, and

navigate to the Decolonization list.

Bibliography

Champagne, Duane. (2007). “In

Search of Theory and Method in American Indian

Studies”. American Indian Quarterly,

31(3), 353–372.

Doxtater, Michael G. (2004). “Indigenous

Knowledge in the Decolonial Era”.

American Indian Quarterly, 28(3/4), 618–633.

Lee, Richard E. (1999). “The

Crisis of the Structures of Knowledge: Where Do

We Go from Here?” Presentation delivered

at the Centre for Developing-Area Studies

Workshop: “Social Sciences and

Interdisciplinarity: Latin American and Canadian

Experiences,” McGill University, Montréal,

Canada, September 23–26, 1999.

—————. (2000). “The

Structures of Knowledge and the Future of the

Social Sciences: Two Postulates, Two

Propositions and a Closing Remark”.

Journal of World-Systems Research, 3,

786–796.

————— . (2008). “Cultural

Studies, Complexity Studies and the

Transformation of the Structures of Knowledge”.

Cultural Science, 1–17.

Simpson, Leanne R. (2004). “Anticolonial

Strategies for the Recovery and Maintenance of

Indigenous Knowledge”. American

Indian Quarterly, 28(3/4), 373–384.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. (1997). “The

Structures of Knowledge, or How Many Ways May We

Know?” Presentation at “Which Sciences

for Tomorrow? Dialogue on the Gulbenkian Report:

Open the Social Sciences,” Stanford University,

June 2–3, 1996.

Wilson, Waziyatawin Angela. (2004). “Indigenous

Knowledge Recovery is Indigenous Empowerment”.

American Indian Quarterly, 28(3/4),

359–372.

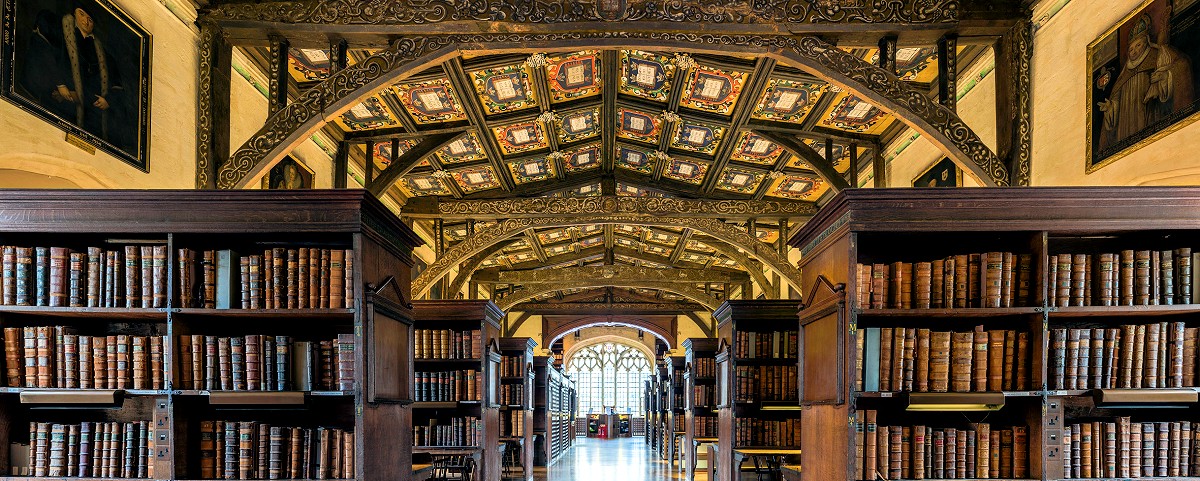

Image: Photo of the interior of

Duke Humphrey's Library, the oldest reading room of

the Bodleian Library in the University of Oxford, by

David Iliff, 2015. From

Wikimedia Commons.

HOME |

SITE MAP |

ABOUT

| RESEARCH |

MEDIA |

ARTICLES |

REVIEWS |

COURSES |

ZAP SITES |

CONTACT

©

2011-2020, Maximilian C. Forte.

|