|

The Zero Anthropology Project

Webfolio for Maximilian C. Forte

HOME

|

SITE MAP

|

ABOUT

|

RESEARCH

|

MEDIA

|

ARTICLES

|

REVIEWS

|

COURSES

|

ZAP SITES

|

CONTACT

CASCADURA from Maximilian Forte on Vimeo.

Cascadura: Colonial, Local, Cosmopolitan

Roi Kwabena’s

spoken word poem, “Cascadura,” begins “simply”

enough, by representing a version of the locally

famous Trinidadian legend that attributes

magical power to the cascadura fish:

those who eat it are destined to return—and not

just return, but to end their days in Trinidad.

There is a poem of the legend, by Allister

Macmillan (Source: History of the West Indies

by Allister Macmillan, Nelson’s West Indian

Readers, Compiled by JC Cutteridge, Book III,

Lesson 9, Pg 42, 43; 1984 Nelson Caribbean), as

reproduced by Guanaguanare:

Those who eat the cascadura will, the native

legend says,

Wheresoever they may wander, end in Trinidad

their days.

And this lovely fragrant island, with its

forest hills sublime,

Well might be the smiling Eden pictured in

the Book divine.

Cocoa woods with scarlet glory of the

stately Immortelles,

Waterfalls and fertile valleys, precipices,

fairy dells,

Rills and rivers, green savannahs, fruits

and flowers and odours rich,

Waving sugar cane plantations and the

wondrous lake of pitch.

Oh! the Bocas at the daybreak—how can one

describe that scene!

Or the little emerald islands with the

sapphire sea between!

Matchless country of Iere, fairer none could

ever wish.

Can you wonder at the legend of the

cascadura fish?

In some ways, the late anthropologist and

cultural activist

Dr. Roi Kwabena uses the same basic

theme: enchantment, love, return, and a

catalogue of the everyday beauties in which

Trinidadians revel. This piece brings into focus

the shared, everyday love of all the things that

make daily life in Trinidad, the unquenchable

desire to return, to revel in the sights,

sounds, smells, tastes, and touch of Trinidad.

Yet his spoken word poem becomes even more

complicated. This combination of the colonial,

the traveler, the visitor, the local, the

migrant, all combine I think to produce a

locally rooted, locally shaped cosmopolitanism,

not universal but accessible to all with some

depth of experience in Trinidad.

Guanaguanare, mutual friend of Roi and myself,

has taken the time to produce the

full transcript of Roi’s poem.

First,

who is the speaker? Is there only one voice?

The poem by Roi Kwabena is first spoken by

someone with the accent and the polite and

affected elite tone of the colonial foreigner.

This person has a cook, Singh. The speaker says

that she would not ban neither Hosay nor

Ramleela, which suggests she has this power, and

that she has a somewhat patronizing appreciation

of local cultural performances. The original

legend itself seems directed at those who would

come and go from Trinidad, but could arguably

extend to natives themselves who migrate. But

clearly there is another speaker in this poem,

even referring to himself directly, “Me,

throwing mangoes….”. He lists all of the simple,

rich wonders of life in Trinidad, seemingly

common and everyday types of things—these are

shared reference points for all Trinidadians,

and probably all Trinidadians abroad could and

do reproduce such lists when thinking back

nostalgically about home, what they miss most,

what they remember, and what they would like to

do when they return. (True to his word, Roi did

end his days in Trinidad: his ashes were

scattered at Mayaro.) This raises another

dimension of the poem, as follows.

Second,

what is the tense? The poem seems to lack

a tense, which seems deliberate. On the one

hand, memory is implied, in returning. There is

a future: when one ends one days. But there is

also lived everyday experience: the list of

Trinidad’s wonders, which can also be stated

from memory, or because one is actually

experiencing them in the present. These

ambiguities in mind, I chose to portray a

certain chronology in the poem: past experience,

memory, return, reintegration.

The Visual Method

Animating a spoken word poem is always

difficult, especially if the aim is to bring out

even more ethnographic depth, simply because the

visual always adds another narrative beyond the

spoken (which also contains within it evocations

of the visual and brings into play all of the

other senses by imaginary means). The problem

can be that the visual

animator—myself—inadvertently adds other

meanings, conjures up different associations,

and inserts a narrative other than what the

original author chose (this brings up

collaboration, next).

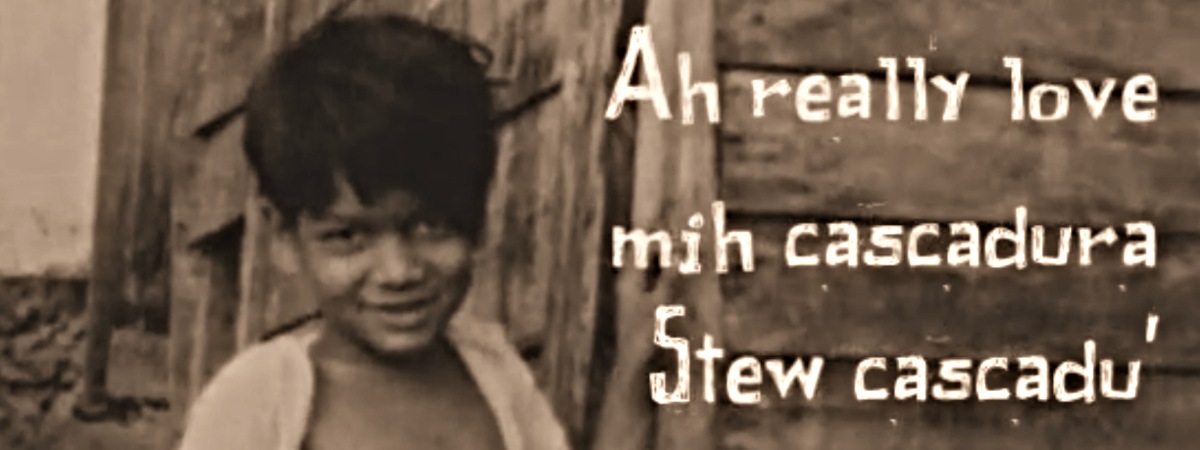

Given some of the considerations above, this is

an explanation of the choices made. The “white

woman” who appears in the video is the

representation of the elite, colonial foreigner

who falls in love with Trinidad and vows to end

her days there. Local steel pan players and

other musicians can be taken as representations

of Roi. The local children at one point,

smiling, pointing at the camera, are there as if

to call Roi back home. Hence the view from an

airplane wing, moving from memory of the past

(depicted via grainy, sometimes sepia-coloured

archival footage), to the present–and thus a

shift occurs in space and time, depicted by a

shift from black and white to colour. Once

returned, full colour and contemporary scenes

are shown via personal video footage taken

during Carnival 1998.

Collaboration?

This joint production was not a collaborative

effort, in the sense that the animation and

visualization occurred well after Roi’s death

and without the benefit of his advice and

guidance. That means that to the extent the

piece is enjoyed and appreciated, the credit

goes to Roi, and where its failings appear, then

only I can take the blame.

Cascadura was the very first spoken word

poem recording that Roi sent to me back in 2006.

I have had many years to listen to it countless

times, and early on Roi and I exchanged some

correspondence about this work. I knew Roi at

first as a publisher, writer, and activist, so

this opened up a whole new dimension to my

appreciation of the breadth of his commitment

and creativity. As someone who has spent many

years in Trinidad, living, studying, and doing

research in the country, I am hoping that I was

able to interpret Roi’s spirit as best as

possible, while working with inevitable

limitations in terms of the footage available to

me.

HOME

|

SITE MAP

|

ABOUT

|

RESEARCH

|

MEDIA

|

ARTICLES

|

REVIEWS

|

COURSES

|

ZAP SITES

|

CONTACT

©

2011-2020, Maximilian C. Forte.

|