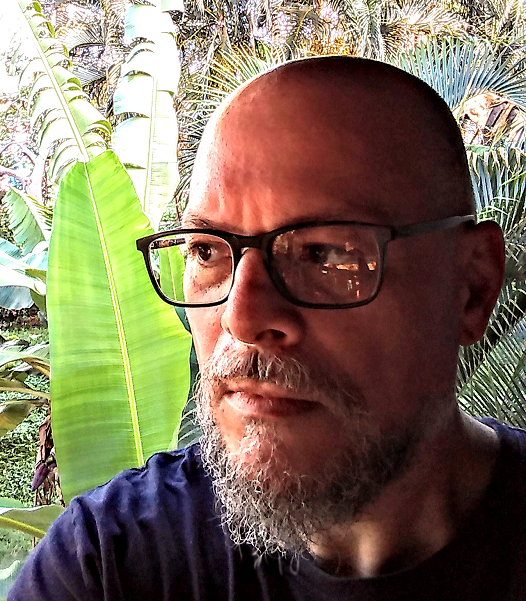

I am a Professor of Anthropology in the

Department of Sociology and Anthropology at

Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. I

received an Honours B.A., with a double major in

Latin American & Caribbean Studies, and

Spanish Language, Literature, and Linguistics

(including Latin America) at York University,

from which I graduated in 1990, summa cum

laude. I then decided to move to Trinidad &

Tobago, where I enrolled in the post-graduate

diploma program at the Institute of

International Relations at the University of the

West Indies, St. Augustine. I obtained a Diploma

in International Relations with

Distinction. After completing the one

year program, I continued into the start of the

M.Phil program, which I discontinued after two

years.

I was in Trinidad from 1990 until 1993.

In 1994 I began a M.A. in Socio-Cultural

Anthropology at the State University of New

York at Binghamton, where I also continued and

developed my interests in world-systems analysis

by taking courses in other departments with

Immanuel Wallerstein, Giovanni Arrighi, and

Anthony King.

I also completed the first year of

the Ph.D program there, but then moved to

Australia, where from 1997 through 2001 I

completed my Ph.D in Anthropology at the

University of Adelaide. I then moved back again

to Trinidad & Tobago, where I remained until

2003, and eventually achieved Permanent Resident

status, the first step on the way to gaining

Trinidadian nationality. In 2003 I took up my

first tenure-track position in Anthropology, in

the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, at

what was then called the University College of

Cape Breton (the name changed to Cape Breton

University in my final months there). In 2005 I

accepted an offer for a second tenure-track

position, in the Department of Sociology and

Anthropology at Concordia University in

Montreal, where I received tenure and have since

been promoted to full Professor. I remain

attached to my interdisciplinary background, and

most of my research has not fallen neatly within

any one discipline. I continue to remain

conversant with a great deal of work done by

non-anthropologists.

I am a Professor of Anthropology in the

Department of Sociology and Anthropology at

Concordia University in Montreal, Canada. I

received an Honours B.A., with a double major in

Latin American & Caribbean Studies, and

Spanish Language, Literature, and Linguistics

(including Latin America) at York University,

from which I graduated in 1990, summa cum

laude. I then decided to move to Trinidad &

Tobago, where I enrolled in the post-graduate

diploma program at the Institute of

International Relations at the University of the

West Indies, St. Augustine. I obtained a Diploma

in International Relations with

Distinction. After completing the one

year program, I continued into the start of the

M.Phil program, which I discontinued after two

years.

I was in Trinidad from 1990 until 1993.

In 1994 I began a M.A. in Socio-Cultural

Anthropology at the State University of New

York at Binghamton, where I also continued and

developed my interests in world-systems analysis

by taking courses in other departments with

Immanuel Wallerstein, Giovanni Arrighi, and

Anthony King.

I also completed the first year of

the Ph.D program there, but then moved to

Australia, where from 1997 through 2001 I

completed my Ph.D in Anthropology at the

University of Adelaide. I then moved back again

to Trinidad & Tobago, where I remained until

2003, and eventually achieved Permanent Resident

status, the first step on the way to gaining

Trinidadian nationality. In 2003 I took up my

first tenure-track position in Anthropology, in

the Department of Anthropology and Sociology, at

what was then called the University College of

Cape Breton (the name changed to Cape Breton

University in my final months there). In 2005 I

accepted an offer for a second tenure-track

position, in the Department of Sociology and

Anthropology at Concordia University in

Montreal, where I received tenure and have since

been promoted to full Professor. I remain

attached to my interdisciplinary background, and

most of my research has not fallen neatly within

any one discipline. I continue to remain

conversant with a great deal of work done by

non-anthropologists.

In the past I have also lived in Italy, and

spent extended periods in England, as well as

French Polynesia. My first language was Italian,

which I continue to speak, in addition to later

learning Spanish, and I have a reading ability

in French. I still consider Trinidad to be my

real home, and my friends and in-laws remain

there. I am both a Canadian and Italian/EU

citizen.

TEACHING INTERESTS

For all of my courses, please click on

courses.

RESEARCH INTERESTS

My current areas of research interest are:

(1) The anthropology of contemporary

imperialism. Can there be an anthropology of

imperialism, and if so, what would it look like?

What is the relationship between anthropology

and imperialism, both historically and

currently? What challenges does imperialism pose

to the constitution of the social sciences as

several, specialized disciplines? How does

imperialism relate to fundamental matters of

“the human condition”? Within this broad stream,

I am looking at the contemporary culture and

political economy of imperialism, down to

everyday life, and in the form of what some have

called the “New Victorianism”. This is meant to

incorporate and build on my work on the “New

Imperialism”. Additional areas of interest focus

on globalization, (anti) free-trade, populism,

and working-class issues.

With reference to neoliberal capitalism (and its

downfall), I am interested in how neoliberalism

permeates contemporary North American society

down to “everyday life”. Alienation, bleakness,

and the revitalization of self-determination,

have been of especial concern to me, but what

are also important are the practices of everyday

life, with my interests ranging from the quest

to own a home, mortgages/credit/personal debt,

the nature of contemporary suburban and

inner-city working-class life, and broader

issues of democratization and local control. In

connection with the New Imperialism, I have also

focused on the role of politically-directed and

mass mediated demonization of challengers to the

dominant system. In connection with the New

Victorianism, I maintain my interest in

“humanitarian interventionism” and “protection”

as neoliberal and neocolonial principles of

abduction, as a globalization of residential

schooling and a renewal of the civilizing

mission, while advancing the interests of

capital.

(2) The history of anthropology. I am

particularly interested in the development of

Canadian anthropology/anthropology in Canada,

and questions of cultural and specifically

academic imperialism. This is also part of my

broader interest in the political economy of

knowledge production, with a focus on academia

in Canada. I examine the contemporary North

American university as an institution of power,

and I am interested in the maintenance of the

current institutional form, its management

practices, and its discipline(s).

(3) The history of trade and other exchanges

between the Atlantic Canada and the Caribbean,

especially in the triangular trade of the

plantation era. To begin, the focus will be on

the role of rum, and how rum helped to “make”

parts of Atlantic Canada, with special reference

to Cape Breton. This is historical research,

which is based on archival and published

sources. The broader aims here are to further

develop work in the fields of history of the

Atlantic World, mercantilism and broader trade

issues, globalization, settlement, the

working-class in Atlantic Canada, the

development of regional and national identities

in Canada, and a broadening of what is commonly

demarcated as “Caribbean history”. I thus expect

to spend much more in time in Nova Scotia, New

Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, and

Newfoundland over the coming years.

And, in a fresh return to some of my older areas

of research:

(4) Indigenous resurgence in the Caribbean,

with a special interest in transnational

Indigenous networking among Caribbean Indigenous

communities in the Anglophone Caribbean in

particular, and the representations of

Amerindian heritage in Trinidad, Grenada, St.

Vincent, and Dominica.

In summary then, my chief concerns are

“globalization” (broadly understood) and the

development of a Canadian perspective on global

and local social problems.

Key words: imperialism, globalization,

neoliberalism, cosmopolitanism, nationalism,

nativism, revitalization, populism, New

Victorianism, New Imperialism, working class,

Atlantic Canada, Maritimes, Caribbean, trade,

history.

Research Achievements

If asked to outline what I think are the main

achievements of my career, I would list them as

follows (roughly in chronological order):

-

Challenging and changing dominant social

science and historiography on the Caribbean,

by revising the post-Conquest cultural

history of the Caribbean, and revealing the

ideological foundations of many narratives

of extinction and absence. In addition,

conducting extended ethnographic research

with contemporary Indigenous communities in

Trinidad, Dominica, and online. Numerous

scholars have followed suit.

-

Founding one of anthropology’s first

peer-reviewed open-access journals—KACIKE:

The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History

and Anthropology (1999-2010). It is

now

archived, and the articles are offered

via

EBSCOhost.

-

Founding the

Caribbean Amerindian Centrelink

(1998-2009), and associated sites, featuring

previously little known ethnographic and

ethnohistoric information on the wider

Caribbean region’s Indigenous Peoples,

island and mainland, past and present. It is

now archived online in three different

forms:

first,

second,

third.

-

Expanding anthropology in the direction of

studying contemporary imperialism, focusing

specifically on US empire. Related to that:

investigating the interrelationships between

imperialism and anthropological knowledge

production.

-

Slouching Towards Sirte: NATO’s War on Libya

and Africa.

-

Attempting to re-establish a Canadian

anthropological approach, both in theory and

in research/writing practice.

-

Developing an alternative press for

anthropology, one that also operates in

dialogue with members of the broader public

and their publication/alternative media

platforms.

Past (and Renewed) Research (1994–present): An Overview

The following is a summary of the the dominant

research questions, arguments, and findings at

the core of my research and publication over

more than a decade, organized in the

chronological order in which the research was

published. What I consider to be my major or

most representative publications in each area of

my research are listed here as well.

In Ruins of Absence, Presence of Caribs:

(Post) Colonial Representations of Aboriginality

in Trinidad and Tobago (Gainesville, FL:

University Press of Florida, 2005), I questioned

and challenged conventional social science and

the cultural history of the Caribbean for

depicting the post-conquest cultural development

of the Caribbean as one based on the presumed

absence or erasure of the Indigenous. My main

research questions in that work were:

-

Why does “Carib” still exist as a category

and as an available identity in Trinidad?

-

What were, and what are, the conditions that

make possible the reproduction of Carib as

an identity and as a historical canon?

-

What value does Caribness hold, and to whom,

when, and why?

One of the main purposes of writing that book

was to bring attention to a field of Caribbean

studies that had been severely neglected, that

is, contemporary Indigenous Peoples of

the Caribbean. In addition, another intention

was to redress certain gaps in anthropological

research on Indigenous Peoples by focusing on

the political and economic processes that can

serve to constitute and define what is

indigenous, and I did so by locating the

indigenous within wider global and historical

contexts, and of course by examining largely

ignored resurgent groups in a region that was

long presumed to be lacking precisely such an

indigenous presence.

Within Ruins of Absence, Presence of Caribs,

my research and writing also went into several

related directions, involving a focus, for

example, on: tradition, memory, and history;

labels and the politics of representation; the

role of state institutions and government acts

in fostering a national identity that frames

indigeneity; the role of the mass media and

internet in bringing attention to, and

circumscribing contemporary indigenous

identities; and, the impact of globalization. In

that work, I also began to develop what I called

“the political economy of tradition” (with more

published later in “The Political Economy of

Tradition: Sponsoring and Incorporating the

Caribs of Trinidad and Tobago,” Research

in Economic Anthropology, 2006, 24,

329–358). The two main elements of this

political economy of tradition were: (1) the

politics and economics of associating certain

values with particular cultural representations

pertaining to individuals marked as members of

specific peoples; and, (2) legislated

recognition and rewards for groups engaged in

often competitive and even conflicting cultural

display. Also from within Ruins of Absence,

Presence of Caribs, I began to do more work

in the areas of globalization and

cosmopolitanism. I first began by looking at how

the Caribs of Trinidad reworked, reinterpreted,

and represented their indigeneity both in and

through a globalized network or organized

representations of indigeneity (or

aboriginality). I brought attention to the

legitimating and value-adding impacts of the

Caribs’ transnational connections, within the

Trinidadian social context. I also examined the

development of new ritual performances that

embodied and enacted the Caribs transformation

into internationally visible “First Nations”.

Given that a large part of my research on the

Caribs in Trinidad was historical in addition to

ethnographic, and involved nearly two years of

work in archives, I mounted a substantial

analytical and empirical critique of received

social science scholarship and previous colonial

narratives that had dominated for centuries and

stressed the extinction of Indigenous Peoples

across the Caribbean, and even in Trinidad which

is mere miles from the South American mainland.

This research found expression in numerous

forms, one of the first being a research paper

produced for my Carib hosts, “How the

Amerindians of Arima Lost Their Lands: Notes

from Primary and Other Historical Sources,

1802–1880,” submitted in 2003. In addition,

a pair of seminar papers, later published as

proceedings and eventually placed online, were

produced for two successive symposia on History

in the Atlantic World at Harvard University: “Writing

the Caribs Out: The Construction and

Demystification of the ‘Deserted Island’ Thesis

for Trinidad” (2004) and “Extinction: The

Historical Trope of Anti-Indigeneity in the

Caribbean” (2005). Related research was

presented as, “The Carib Presence:

Post-Colonial Re-encounters with Trinidad’s

Indigenous Peoples,” at the American Society

for Ethnohistory in 2004. Arguably the strongest

piece of work to come out of this branch of my

research was: “Extinction: Ideologies Against

Indigeneity in the Caribbean” (The

Southern Quarterly, 2006, 43(4), Summer,

46–69), which offered a systematic and detailed

rebuttal of the discourses, narratives, and

empirical data that had been advanced in support

of extinctionist theses developed over centuries

in the Caribbean and outside the region. My

ethnohistoric research on the Caribs of Trinidad

and the wider Caribbean region led to the

invited publication of three encyclopaedia

entries on this subject as well as the field of

Caribbean postcolonialism, each published in

2011 by ABC-CLIO: “Carib Slavery—Spanish

Colonial Control over Caribbean Labor” in

World History Encyclopedia, Era 6: The First

Global Age, 1450–1770; “The Caribbean and

Postcolonialism” in World History

Encyclopedia, Era 9: Promises and Paradoxes,

1945-Present; and, “Indigenous People of

the Caribbean since 1945” in World

History Encyclopedia, Era 9: Promises and

Paradoxes, 1945-Present. Regionalizing

research on Caribbean indigeneity was at the

heart of my edited volume, Indigenous

Resurgence in the Contemporary Caribbean:

Amerindian Survival and Revival (New

York, NY: Peter Lang USA, 2006). The arguments

presented in the volume hinged on an

understanding that acknowledgment of the

presence of the indigenous in Caribbean

societies significantly challenges our

understandings of the cultural complexity of the

modern Caribbean. In addition, we revealed how

some of the same political and economic

processes that had the effect of marginalizing

contemporary Indigenous Peoples could sometimes

provoke if not enable their reproduction as

indigenous entities. Until then, a volume

focused exclusively on the contemporary

Indigenous Peoples of the Caribbean simply did

not exist, and has yet to be rivalled.

In one of my chapters in Indigenous

Resurgence (above) titled, “‘In This

Place Where I Was Chief’: History and Ritual in

the Maintenance and Retrieval of Traditions in

the Santa Rosa Carib Community of Arima,

Trinidad,” we asked the following questions:

-

To what extent do the Caribs of Trinidad

speak of “survival”?

-

What do they mean by “revival,” does it

differ from “survival”?

-

Is there a Carib perspective on tradition

and history?

One of the main highlights in that chapter,

pertaining to the concept of tradition, was a

sequence of explanations of Carib concepts of

cultural resurgence, ranging from survival to

revival, maintenance, retrieval, reclamation,

and interchange. In another of my chapters in

that volume, “Searching for a Centre in the

Digital Ether: Notes on the Indigenous Caribbean

Resurgence on the Internet,” I joined the

still nascent field of “cyber ethnography,”

which I would later teach as a course, and which

took my work into yet another direction. In that

chapter I first outlined how select individuals

were using the internet to document, verify, or

give voice to their self-identification as

Indigenous, to make themselves more visible, and

in some cases going in search of a sense of

“community”. Secondly, I examined how the

internet served as another “membrane” for

collecting stories and images of one’s tribe,

transmitting them directly to others, and thus

aiding in the reproduction of indigeneity by

long-distance means, especially important for

individuals separated from their places of birth

due to out-migration. Thirdly, I explored how

the internet aided in the development of a

transnational indigenous movement and how

certain symbols, motifs, and narratives of

indigeneity were not only shared, but shared

unequally, so that certain representations of

indigeneity dominated over others. In other

sections of the chapter, I also tied the

research to a body of existing literature on

community and interaction in cyberspace, while

connecting the work to my own online practice in

developing the Caribbean Amerindian

Centrelink. Looking at both the constraining

and enabling, creative and restrictive features

of indigeneity practiced in cyberspace, as well

as the representation of anthropological

research and advocacy in cyberspace, and the

ethical questions raised, my research resulted

in further invited publications, such as “Amerindian@Caribbean:

The Modes and Meanings of ‘Electronic

Solidarity’ in the Revival of Carib and Taino

Identities,” in Kyra Marie Landzelius’

unique volume, Native on the Net: Indigenous

and Diasporic Peoples in the Virtual Age (Routledge,

2006); “Centering the Links: Understanding

Cybernetic Patterns of Co-production,

Circulation and Consumption,” in Christine

Hine’s volume, Virtual Methods: Issues in

Social Research on the Internet (Berg,

2005); and, “Co-Construction and Field

Creation: Website Development as both an

Instrument and Relationship in Action Research,”

in Elizabeth Buchanan’s volume, Virtual

Research Ethics: Issues and Controversies

(Idea Group, 2004). There was also a related

encyclopaedia entry that I produced, “Website

Development as Both an Instrument and

Relationship in Action Research,” in The

Encyclopedia of Developing Regional Communities

with Information and Communication Technology

(2005).

The globalization/transnationalism line of

research took a turn into the related area of

cosmopolitanism and transculturation in my

edited volume, Indigenous Cosmopolitans:

Transnational and Transcultural Indigeneity in

the Twenty-First Century (New York, NY:

Peter Lang Publishing, 2010). I was motivated in

part by a concern that any attempt to forge an

opposition between indigeneity/indigenism and

cosmopolitanism would be an effort contrived

without basis in the historical, social, and

cultural realities at the root of Indigenous

ways of seeing and being in the world. However,

I also recognized that this debate was not so

much one that stemmed from Indigenous actors

themselves, as much as it was a debate internal

to anthropology, with consequences for how

anthropologists seek to represent the worlds

about which we claim to possess important

comparative knowledge. The attempt here was to

bring forth non-Eurocentric perspectives on

cosmopolitanism in contrast with much of what

constitutes received thinking on

cosmopolitanism. Along with the contributors, I

argued that Indigenous forms of cosmopolitanism

not only unfold in the present, but they also

predate formal European conceptualizations of

what it means to be cosmopolitan. The dual

understanding advanced here was that of

Indigenous Peoples as both rooted yet also

reproducing their ways of living and ways of

thinking through various routes of transnational

and transcultural experience. Four principal

questions were explicitly raised in this

research project:

-

What happens to Indigenous culture and

identity when being in the “original place”

is no longer possible?

-

Does displacement, in moving beyondone’s

original place, mean that indigeneity

diminishes or vanishes?

-

How are being and becoming Indigenous

experienced and practiced along diverse

transnational/translocal pathways?

-

How are new philosophies and politics of

Indigenous identification constructed in

new, translocal settings?

In one of my chapters in that volume, “A

Carib Canoe, Circling in the Culture of the Open

Sea: Submarine Currents Connecting Multiple

Indigenous Shores,” I discussed

cosmopolitanism as both rooted in and routed

through specific settings, so that the “people

of the sea” became more than just a metaphor but

rather it indicated a context of local and

regional cosmopolitan practice that extends

centuries back in time and circulates around an

actual sea. The project above hinted at the

problems of trying to confine and categorize

indigeneity, problems that were more directly

confronted in another body of work that began to

develop at roughly the same time. Here I am

speaking of my work in three chapters of my

edited volume, Who Is An Indian? Race,

Place, and the Politics of Indigeneity in the

Americas (Toronto, ON: University of

Toronto Press, 2013). The purpose of that

project was to compare and theorize contemporary

policies, ideologies, and technologies for

regulating, certifying, and administering

Indigenous identifications, and the alternatives

for indigeneity beyond biologized determinants.

There were three main aims, presented here in

ascending order of importance. The first

involved recognition of the need to move beyond

the telling of local stories of calculations of

indigenous identity, toward a more comprehensive

analytical methodology embracing the Americas,

thereby promising fertile ground for

conceptualizations of what are often striking

similarities coupled with theoretically fruitful

analysis of differences. Thus one aim was to

produce a transnational way of talking about

race and indigeneity in the Americas. The second

aim was the theoretical development of a

unified, Americas-wide, problematic which can be

termed the bio-politics of indigeneity, focused

on race (phenotype), blood, and DNA analysis.

The third aim involved theorizing the current

practices and future possibilities of

indigeneity beyond the restrictions of bodily

markers. Rather than simply answer the question,

“Who is an Indian?” I went about explaining why

historically this has been both an influential

question, and yet a terribly flawed one. Such a

question implied power, history, taxonomy,

ontology, positionality, and science—each of

which were scrutinized in this volume, with

remarkable findings of commonalities across the

Americas. Specific research questions addressed

in this project were the following:

-

Is the “real Indian” a construct that

appears across the Americas, and if so, does

it take different forms?

-

Do racial characterizations of Indigenous

identity, especially in terms of

phenotypical appearance, prevail in places

where “Indigenous” has (not) been defined in

state law?

-

Are there diverse conceptualizations of

“race,” both in the dominant societies and

among Indigenous persons, and how do these

confront each other?

-

Is the concern with mapping identities a

by-product of the resurgence Indigenous

identification?

-

What issues of power and citizenship are

tied up with ways of narrating Indigenous

identity in terms of the body?

-

What are the historical contexts and

political and economic frameworks that work

to secure, reproduce, or transform these

modes of identifying the Indigenous?

-

What options are there for new ways of

being/becoming Indigenous under current

regimes of certification, classification,

and surveillance?

-

In the absence of a strong basis in visible

racialized difference, how do some

Indigenous persons go about articulating

their own identities?

-

How are collective and individual claims to

Indigenous identity similar and different?

-

How does the definition of Indigenous

identity change when it is communicated to

different audiences?

In one of my chapters for this volume, “Carib

Identity, Racial Politics, and the Problem of

Indigenous Recognition in Trinidad and Tobago,”

the contents followed three basic lines of

argument. First, that the political economy of

the British colony dictated and cemented

racializations of identity. Second, the process

of ascribing Indigenous identities to

individuals was governed by the economic rights

attached to residents of missions, rights which

were cut off from any miscegenated offspring.

There were thus political and economic interests

vested in the non-recognition of Caribs, and

race provided the most convenient

justification—a justification that took the form

of a narrative of extinction. Third, over a

century later, while racial notions of identity

persist, current Carib self-identifications

stress indigeneity as a cultural heritage, an

attachment to place, a body of practices, and

recognition of ancestral ties that often

circumvent explicitly racial schemes of

self-definition. State recognition of the Caribs

occurs within this historical and cultural

context, and therefore imposes limits and

conditions that simultaneously create new forms

of non-recognition. In another of my chapters in

the same volume, “Seeing Beyond the State and

Thinking beyond the State of Sight,” I

outlined the four main axes by which social

scientists, policy-makers, administrators,

journalists, and (Indigenous) activists among

others, have organized their political

classifications or representations of Indigenous

identities. I explained and summarized these as:

anti-Indigenous anti-essentialism;

anti-Indigenous essentialism; pro-Indigenous

essentialism; and, pro-Indigenous

anti-essentialism. This last volume basically

brought to a close (for the foreseeable future)

of my series of book, chapter, and article

publications on Caribbean indigeneity.

In

2019, with the publication of Arima Born:

Revealing the History of Arima and its Mission

through the Catholic Church’s Baptismal

Registers, 1820–1916, I returned to some

of my earlier research foundations by completing

a project that, off and on, had been 20 years in

the making. In 1998 I began archival research

with a focus on the baptismal registers of the

Arima Mission then housed in the Santa Rosa

Roman Catholic Church in Arima. In a written

commitment to the leadership of what was then

called the Santa Rosa Carib Community (now the

Santa Rosa First People’s Community), I promised

to organize and share my findings from the

baptismal registers. In preparing the files I

realized that a larger story—a

set of stories in fact—came into focus, enough

to necessitate a book-length production rather

than a simple file or report. What framed the

baptismal data was the history of the Mission as

a labour-exploitation scheme that functioned as

an adjunct to the slave plantation economy—and

it was a history shrouded in persistent

Amerindian resistance to Christian assimilation.

It thus appears that one of the motives for

colonialist narratives to write out the

Amerindians from history was out of

embarrassment for the obvious failure of their

“civilizing mission”. A great deal of the

history of the foundation of modern Arima, as a

slave colony, also came to light.

Current Research (2008–2015–the present): An

Overview

Given my accumulated research pertaining to

broad issues involving colonialism, imperialism,

warfare, and ethnography, from late 2007 my

attention began to focus on recent developments

concerning attempts to recruit social

scientists, and especially anthropologists, in

military-run counterinsurgency programs, the

increased presence of military-funded research,

and state intelligence agencies’ recruitment of

academics in the UK and then Canada. This field

of research entails numerous implications for

research ethics, the reputation and safety of

anthropologists, and the decolonization of

social science. My engagement in this area found

numerous expressions, ranging from the invited

publication of my entry, “Ethnography” in

the International Encyclopedia of the Social

Sciences, 2nd ed.; three conference

presentations (“(Re)Imperializing

Anthropology and Decolonizing Knowledge

Production,” 2008; “‘Useless

Anthropology’: Strategies for Dealing with the

Militarization of the Academy,” 2009; and, “The

Anthropology of Militarism/The Militarization of

Anthropology,” 2011), one invited

presentation, “The Anthropologist in Mined

Fields,” at the Department of Anthropology,

Université de Montréal, 2009; and three

articles/chapters: “The Human Terrain System

and Anthropology: A Review of Ongoing Public

Debates,” published in the American

Anthropologist (113[1], March, 2011,

149–153); “Anthropology against Empire:

Demilitarizing the Discipline in North America,”

published in Emergency as Security: Liberal

Empire at Home and Abroad (2013), and an

encyclopaedia entry, “The Human Terrain

System and Anthropological Critiques of the Uses

of Cultural Knowledge in Counterinsurgency”

in International Encyclopedia of Social and

Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. With reference

to the Human Terrain System and the recruitment

of anthropologists in counterinsurgency and

other forms of military-directed research at the

service of the national security state, I also

published over 330 essays and short pieces on

the websites of Zero Anthropology as well

as Anthropologists for Justice and Peace.

In relation to the research efforts and public

engagement above, in 2010 I founded

Anthropologists for Justice and Peace, which

later disbanded in 2013. This initially emerged

out of conference roundtables that I organized

at meetings of the Canadian Anthropology Society

(CASCA), and publishing in CASCA’s newsletter: “Militarizing

Anthropology, Researching for Empire, and the

Implications for Canada” (Culture,

2[2], Fall, 2008, 6-10).

As classified documents published by WikiLeaks

became an important source of information in my

“studying up” the Human Terrain System and

related programs, my work branched off into

analysis of issues of secrecy and the national

security state. One of my first publications in

this area was إعادة اختراع الويكيليكس

المستمرة الإعلام والسلطة وتبديل شكل الاحتجاج ماﺁسيمليان

فورت (“The Ongoing Reinvention of

Wikileaks: Media, Power, and Shifting the Shape

of Dissent”) in WikiLeaks, Media and

Politics: Between the Virtual and the Real

(Beirut: Arab Center for Research and Policy

Studies, 2012). “On Secrecy, Power, and the

State: A Dialogue between WikiLeaks and

Anthropology” was published in Force

Multipliers (Alert Press, 2015). Work

related to the latter chapter was also presented

at the 2011 conference of the American

Anthropological Association in a paper titled, “WikiLeaks

and Anthropology: Secrecy, Power, and the State”.

I also served as a discussant in another session

at the same conference, on “Anthropologies of

the Covert: From Spying and being Spied upon to

Secret Military Ops and the CIA”. A much shorter

commentary on secrecy and state power was

invited by the World Policy Journal in

2013 and published as “Secret from Whom?”.

A significant development in my research began

to take shape as early as 2009 and most

definitely by the start of 2011, involving a

critical historical, theoretical and documentary

examination of the logic, the narratives, the

methods, and the outcomes of militarized

humanitarian interventions, sometimes under the

heading of the “responsibility to protect”. In

some important ways this represented a

transformation and yet a continuation of the

work that preceded this phase of my research.

First, militarization and militarism needed to

be contextualized and not treated as sui

generis phenomena—I identified the context

and proximate cause as being the fortification

of state power and, in the western context,

imperial dominance. Second, I recognized that

this was a development in imperial rationales

and techniques that emphasized humanitarianism,

empathy, and winning hearts and minds, with

determined efforts to appeal to public opinion

by way of the media. In one key respect–the

“humane” element–this work flowed very easily

from my research on the use of social scientists

in counterinsurgency and the stated

justifications for their use. Third, this work

tied into my past research on colonial

civilizing missions conducted by European

conquerors and settlers among Indigenous

Peoples, in the Caribbean and elsewhere, which

also brought me back to imperialism and the

occasional employment of non-state bodies (such

as church missions) to confine and resocialize

captive Indigenous populations. The most

significant outcome of this phase of my research

was my book, Slouching Towards Sirte:

NATO’s War on Libya and Africa

(Montreal: Baraka Books, 2012), which has since

been translated into Japanese and republished in

Japan in 2019.

Continuing from this work, I began to fuse

several lines of my past and current research by

looking at “humanitarian intervention” as

imperial abduction, and specifically as a

globalization of a basic discursive and

strategic template derived from residential

schooling in Canada, and its counterparts in

Australia and the US. This latter phase of my

research found expression in two

well-circulated, though self-published chapters

in my edited volume, Good Intentions:

Norms and Practices of Imperial Humanitarianism

(Montreal: Alert Press, 2014). Some of these

lines of analysis can also be found in my

encyclopaedia chapter, “Imperialism and

NATO’s War in Libya,” in the Palgrave

Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism.

Continuing from this work, I began to fuse

several lines of my past and current research by

looking at “humanitarian intervention” as

imperial abduction, and specifically as a

globalization of a basic discursive and

strategic template derived from residential

schooling in Canada, and its counterparts in

Australia and the US. This latter phase of my

research found expression in two

well-circulated, though self-published chapters

in my edited volume, Good Intentions:

Norms and Practices of Imperial Humanitarianism

(Montreal: Alert Press, 2014). Some of these

lines of analysis can also be found in my

encyclopaedia chapter, “Imperialism and

NATO’s War in Libya,” in the Palgrave

Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism.

Finally,

an auxiliary component of this research involved

refocusing on the relationships between

imperialism and anthropology, which joins

significant new literature published in the area

of sociology and empire. On the one hand, the

“anthropology of imperialism” still barely

exists as a discernible field of inquiry in

North American and European anthropology,

meaning that there is great room for further

development. On the other hand, imperialism is

too important to be left to any one discipline.

Therefore much of my work focused on approaches

that transcend disciplinary boundaries and that

are open to any and all fields of knowledge

production that can be useful in addressing

certain fundamental research questions.

Expressing a renewed critique of the colonial

origins, current imperial collaborations, and

the dilemmas of disciplinary and top-down

research approaches, was my essay, “Anthropology:

The Empire on which the Sun Never Sets” (Anthropological

Forum: A Journal of Social Anthropology and

Comparative Sociology, 24(2), 2014,

197-218). In addition, I have published several

dozen essays in this area on Zero Anthropology.

Finally,

an auxiliary component of this research involved

refocusing on the relationships between

imperialism and anthropology, which joins

significant new literature published in the area

of sociology and empire. On the one hand, the

“anthropology of imperialism” still barely

exists as a discernible field of inquiry in

North American and European anthropology,

meaning that there is great room for further

development. On the other hand, imperialism is

too important to be left to any one discipline.

Therefore much of my work focused on approaches

that transcend disciplinary boundaries and that

are open to any and all fields of knowledge

production that can be useful in addressing

certain fundamental research questions.

Expressing a renewed critique of the colonial

origins, current imperial collaborations, and

the dilemmas of disciplinary and top-down

research approaches, was my essay, “Anthropology:

The Empire on which the Sun Never Sets” (Anthropological

Forum: A Journal of Social Anthropology and

Comparative Sociology, 24(2), 2014,

197-218). In addition, I have published several

dozen essays in this area on Zero Anthropology.

2016–the present:

The bulk of my research is largely divided between the three main

areas outlined at the top of the page, with

periodic returns to elements of my past research.

Indeed, by mid-2019, following an especially

reflective sabbatical, I revisited and reworked

my research program with a fresh return to my

Caribbean research, focusing on indigenism,

indigeneity, and globalization.

Maximilian C. Forte (May, September, 2019)